-

January 19, 2026

January 19, 2026

Note: This story was originally published in the Sept. 21, 2014, issue of the Sooner Catholic, when the Church celebrated 50 years since the signing of the Civil Rights Act

On a steamy Georgia morning in March 1965, Father Eusebius Beltran and three of his brother priests piled into the four-door sedan they borrowed from the Archdiocese of Atlanta and headed south toward Selma, Ala.

It had been two days since they’d heard news of a police shooting and beatings during a protest march in Selma that would later become known as “Bloody Sunday.”

The men were not strangers to marches during the Civil Rights Movement, having marched many times through the streets of Atlanta to protest discrimination by schools, restaurants, bus stations and other public venues. But, they hadn’t marched in a protest like this. The Selma marches became a national spark to protest the ongoing exclusion of African-American voters from the electoral process and from the discrimination they faced.

At the urging of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who they’d spoken with often at his father’s Baptist church, the Catholic priests sought approval from Archbishop Hallinan for the road trip to Selma and use of the archdiocese’s car.

“He told me that he wanted to see the boys, the priests, who were going with me before we left,” said Archbishop Beltran, who is now Archbishop Emeritus of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City.

“The four of us went to see Archbishop Hallinan in the hospital and that’s when he asked us ‘Do you guys know what you’re doing? Do you realize you’re breaking the law? Do you know that you could go to jail? And, that if you go to jail, I want to let you know I will not bail you out because part of standing for the truth is you take the punishment, and that’s part of the punishment.’ We said we all knew that, and he said ‘OK, God bless you.’”

After a nervous 4-hour drive to Selma, the priests each claimed a mattress on the floor of a hallway at the Catholic church and headed to join the crowds at a pre-march pep rally.

“The whole thing was well-organized and there was always a spokesman up there who was giving directions, reminding people no violence and to be ready to take a beating. It was scary in a way, but when you’re young, you don’t think about it. And, it had to be done too. It was part of the movement at that time. Selma brought together everything we were working toward.”

The next day, the march began in the same way it had two days earlier. Dr. King led the way across the Edmund Pettus Bridge where the group of more than 2,500 marchers were met by state troopers. Since a judge had issued a court order prohibiting the marchers from continuing to Montgomery, Ala., they turned around and marched back to the church without incident. (Later that evening, three white pastors were attacked by members of the Klu Klux Klan, killing one Universalist pastor after the public hospital refused treatment.)

Following the second march, which became known as “Turnaround Tuesday,” Father Beltran and his crew returned to Atlanta where they continued their meetings and marches for several years – including a march to protest a segregated chicken restaurant owned by Lester Maddox, who later became Georgia’s governor.

It has been 50 years since President Lyndon Johnson signed the landmark Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin, and ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, at the workplace and by facilities that served the general public.

While there have been significant gains in opportunity, fairness and civil rights, Archbishop Beltran said new clashes such as those in Ferguson, Mo., are most unfortunate. Such protests become violent responses due to a lack of responsibility and civility.

“I use the word responsibility because I’m afraid too many people don’t want to accept responsibility, which is why you have deferred marriage, why you have young men not entering the priesthood, because those are long-term commitments that demand responsibility. … Too often people think that everything centers around them. It should center around our relationships with others, with God,” he said.

“That’s the problem I see with protests today. They turn violent and people who are innocent suffer as a result. Burning stores, looting things, that’s vandalism. It’s not legitimate protest and it’s wrong.”

Reflecting on his trip to Selma nearly 50 years earlier and contemplating what lies ahead for communities around the world, Archbishop Beltran turned to the basic belief of God-given dignity.

“I’m optimistic. I am. I think it will get better,” he said. “Our Catholic faith has always spoken about the dignity of the human person. And, yes, the Catholic Church has made a lot of mistakes and will continue to make mistakes, but basically it has adhered to the strong principles in human rights and the equality of human beings. Love God first, love your neighbor as yourself. That’s what it’s all about.”

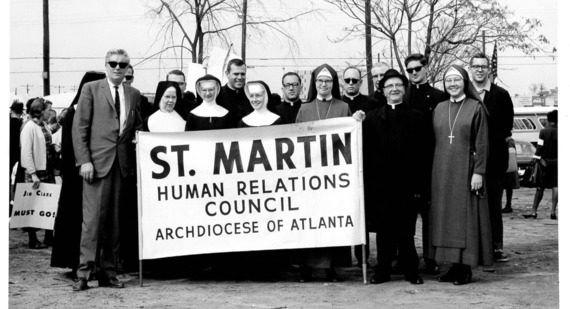

Photo: Fr. Eusebius Beltran (middle) is with the St. Martin Human Relations Council at a demonstration in Atlanta on March 16, 1965, protesting police brutality in Selma, Alabama. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s father, Martin Luther King Sr., was at this demonstration. Photo from The Office of Archives and Records/The Georgia Bulletin, Archdiocese of Atlanta.